News

It

For years, Jessica Zucker, a Los Angeles-based psychologist who specializes in reproductive and maternal mental health, has worked to break through the silence and shame that surrounds miscarriage.

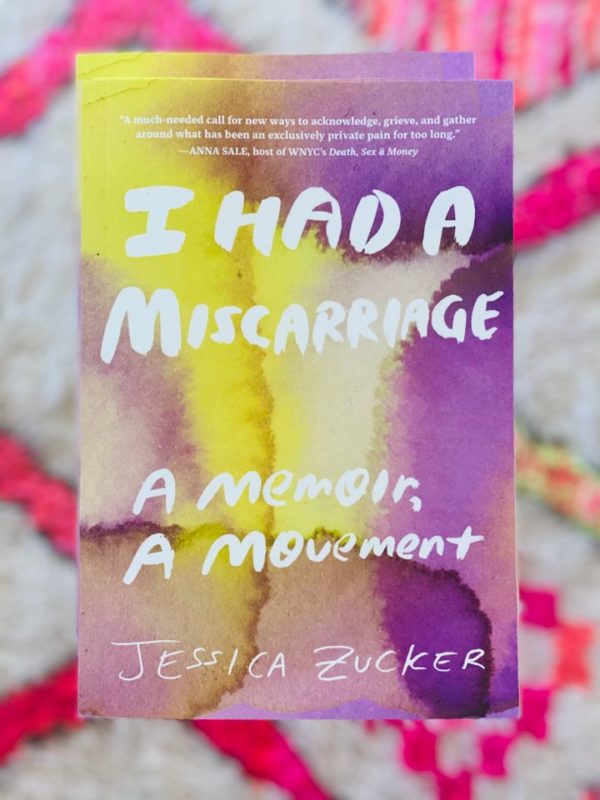

Zucker, who miscarried at 16 weeks while at home and alone, reminds people again and again that miscarriage is not rare. It is a common ― though difficult ― outcome of pregnancy. That’s a message that drove her viral #IHadaMiscarriage social media campaign, which she kicked off in 2014. And it’s a message Zucker explores in-depth in her book, “I Had A Miscarriage: A Memoir, A Movement,” that was released this week.

HuffPost Parents caught up with Zucker to discuss the extent to which conversations around pregnancy loss have emerged from the shadows in recent years, and the ways in which we still fall way short in supporting loved ones through times of pain and trauma.

So much of the work you seem to be doing is simply continuing to normalize miscarriage. Why is that so important to do — and keep doing?

Miscarriage has been taboo, in this antiquated way, over the generations. But we can change that. Now! Once and for all, for ourselves and for future generations.

Why? Because miscarriage is not a disease. There is no cure. It is not going anywhere. It is a normal outcome of pregnancy! I just don’t understand why people don’t understand this. This is a normative outcome of pregnancy, albeit disappointing. It can be traumatizing. One in four pregnancies results in miscarriage. That’s too many people to continue to treat as though they’re an anomaly.

You had a miscarriage at 16 weeks, alone in your bathroom at home, which you describe in a pretty detailed way in the book — talking about what you felt, what you heard, the frantic phone call you had with your doctor who gave you instructions on handling the “medical chaos” of the moment as you put it. Why such a detailed explanation?

Well first, because it’s a memoir. And it’s a memoir about miscarriage.

But I also think that when there’s a topic that’s shrouded in such silence and shame, one of the ways in which we work against that is to do the very thing that our culture may tell us not to do. Which is to explicitly — and unabashedly — share our stories. It’s not a victim thing, it’s not an attention-seeking thing. It’s simply: These are the details of what happened.

I want to invite people into these hard stories, because most of us become a statistic in one way or another. Why are we still so quiet about this?

One thing you’ve worked hard to do through your book, essays, social media — all of it — is to offer guidance about how people can better support women who’ve experienced pregnancy loss. So, what are some basics?

People typically don’t know what to say or what to do based primarily on the fact that, as a culture, we fail to adequately talk about grief. We barely acknowledge it. Especially this particular type of loss. Phrases such as: “At least you know you can get pregnant,” “It wasn’t meant to be,” “God has a plan,” and “Everything happens for a reason” do not help. They shove grief into the outskirts.

The most profound thing we can do for our loved ones in their time of pain is to meet them where they are ― resisting temptations to “fix,” predict the future, or make unsolicited suggestions.

Do say: “How are you?” Don’t say: “It’ll be different next time.” Do say: “If or when you’d like to talk about your experience, I’m here.” Don’t say: “Stay positive.” Do say: “I’m here to support you through whatever it is you are feeling.” Don’t say: “Maybe you should do IVF next time or adopt…”

It’s simple: Say what you imagine you might want to hear if you were in her shoes.

You also point out that women who’ve experienced miscarriage themselves aren’t necessarily better at saying the “right” thing than the rest of us. Why is that?

Well first, I do think loved ones are well-meaning. But there can be a tendency to compare and contrast grief. What would be way more helpful is to huddle up close and simply say: “How are you doing? I’ve been through it too, but I imagine we’ve had different experiences. And I’m here for you right now.”

It’s important to remember the hormonal changes and the mood changes women experience [around miscarriage] are so intense. Whatever people said to me right after my miscarriage has never left my mind. I think people have to be a little more mindful of that ― of just how raw people are right then.

So how do you think we (all of us!) are doing now in terms of normalizing miscarriage and supporting women and their partners?

I’m hopeful. There have been seedlings that have prepared our culture for a potential sea change ― and I hope to be a part of that change.

As for right now, I do think that COVID has exacerbated the preexisting isolation that can accompany miscarriage. The fact that so many people are finding out at their prenatal appointments when they’re on their own adds to the complexity of what they’re navigating. And then if you have to have a D&C and you’re on your own, and communing in the aftermath of that loss is prohibited … I worry that we’ll see in the long run that people will have had to potentially stifle even more of their feelings. And they will feel that much more alone.

This interview has been edited and condensed.