News

I Spent Years Fighting For Control. Then My Son Nearly Died In Childbirth — And I Was Forced To Face A Painful Truth.

I’ve always known I had a problem with control, but it wasn’t until my son faced a near-fatal complication in childbirth that I was forced to come to grips with it.

I arrived at the hospital on a Friday night, unsure of whether my water had broken. I was admitted soon after to labor in the presence of my husband and a sweet 23-year-old nurse with purple hair. A few hours of contractions made the epidural that followed feel like a cakewalk. Then, three hours later, it was time to push.

“I wouldn’t tell anyone about this if I were you,” our obstetrician said with a laugh as I prepared to breathe through the third and final contraction. When I asked what she meant, one of the nurses said that labor hardly ever happened so quickly or easily.

But there were other benefits to a swift delivery. A few minutes later, I was left holding my son against my chest. He’d come out blue, his umbilical cord wrapped around his neck four times and tied in a true knot.

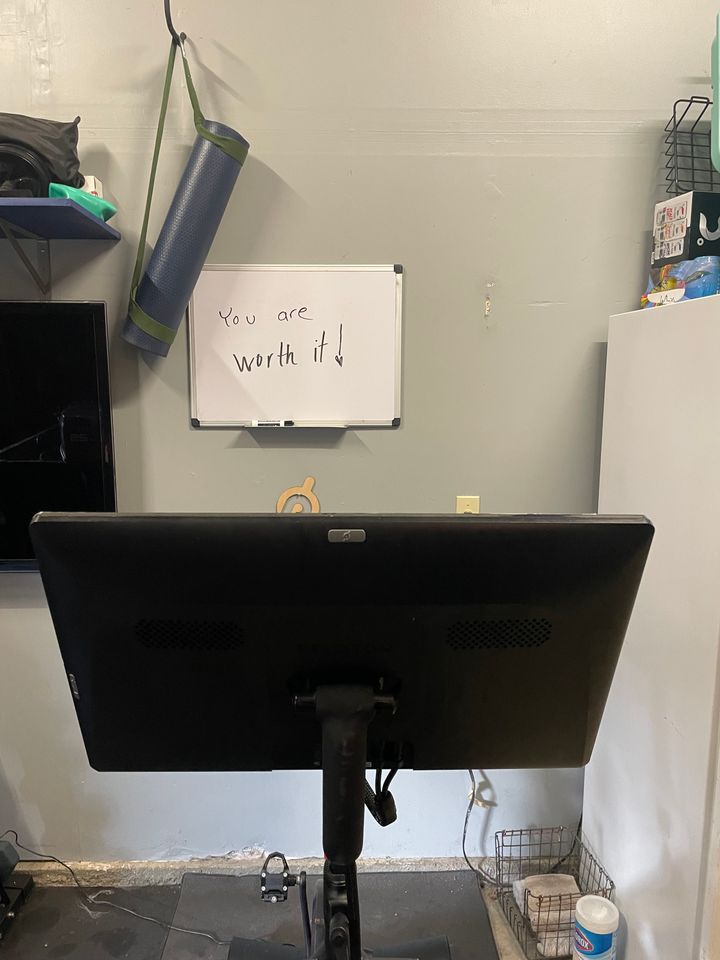

Our doctor had never seen anything like it before. A quadruple nuchal cord. Had the delivery taken any longer, she told us, it would have been a stillbirth. The pregnancy itself had been full of ups and downs, with concerns about preterm labor and a low-lying placenta. I had never felt more vulnerable. But a little over halfway through, I mustered my courage and resolved not to worry any more than I had reason to. To quell my nerves, I found a sense of comfort and control on my spin bike, which I had ridden at least four days a week with my doctor’s encouragement until the day my contractions began.

Our doctor didn’t say anything about the umbilical cord at first, although I’m not sure I would have heard her if she had. She simply placed our son on my chest and worked on delivering the placenta. It wasn’t until she was sure that our son was OK that we were told there had ever been a problem. It was all I could do to register her words.

Our son had arrived, he was with us, he was OK.

Looking down at the wrinkled infant lying naked on my body, I was immediately struck by his beauty and the sense of completion that his birth entailed. He was our miracle baby, the obstetrician proclaimed.

I had my own close call with death early in life while I was still living in the country of my birth, Bulgaria. When I was 3, I watched as my father took my mother’s life and then his own after he threatened to kill us both.

He had flown into a rage after learning that my mother falsely claimed abandonment and divorced him without his knowledge or consent by publishing a notice that went unanswered in the state gazette. At the time, my father was in Sweden, living in a refugee camp and working as a taxicab driver — preparing to move our young family abroad.

My grandmother was awarded custody of me shortly after the tragedy, but she was dying of cancer, and although my paternal family sought to adopt me, it seemed unconscionable to her that I be raised by the family of the same man whom I witnessed kill my mother.

Several years had passed since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, but the region remained unstable — dangerous for a newly orphaned child. Faced with the threat that I would be kidnapped or worse if I stayed in Bulgaria, my grandmother arranged to have me adopted by an American family living in Seattle. I left the country on a need-to-know basis in December 1993. My grandmother died exactly one month later.

My delivery to the United States was tenuous and full of uncertainty, but I survived.

Photo Courtesy Of Mirella Stoyanova

In part a reaction to the initial trauma and in part a reaction to growing up in a highly dysfunctional adoptive family in the years that followed, I spent much of my 20s healing and working on myself. I put myself through graduate school, attended years of therapy and built a life and a career I loved — the dream of becoming a mother propelling me through most, if not all, of it.

But working on myself also enabled me to keep a safe distance from any kind of relationship that threatened further loss or rejection and to hide behind a perfectionistic veneer that I worked tirelessly to uphold — and it reinforced the belief that I was not worthy to be loved as is.

My interest in the underpinnings of my own healing led me to become a therapist. Eventually I met my husband, overcame deep ambivalence about our relationship and got married. Later we decided to start a family of our own.

Some of my old habits remained: a stringent exercise routine, a hustle to achieve and the focus on constant self-improvement, to name a few. I had learned early on that I had limited influence over what happened in life, but I was determined to take control of whatever I could. And though, on occasion, my need for control had caused problems in all of my relationships, including the one with my husband, I had come a long way from believing that I wasn’t supposed to be here.

My story could have ended differently, but it didn’t — the birth of my son, the fullest expression of a life I reclaimed and years spent healing.

I suppose the important part was that my son survived his birth, but for days after he was born I remained haunted by the possibility that he might not have, which in retrospect seemed an apt entry into motherhood. In those early, fragile days, I couldn’t help but run through the list of fortunate occurrences to which we owed his survival. Most notably, it had been lucky that we arrived at the hospital when we did and that my labor had been mercifully short.

I also couldn’t help but wonder whether I had caused the quadruple nuchal cord with my insistence on exercising vigorously on my spin bike throughout my pregnancy. After all, exercise was one way I mitigated the very real feelings I had throughout my pregnancy of not having control over my body. I couldn’t deny the possibility that my desire to protect myself from the discomfort of my own vulnerability could have very directly been to blame for the threat our son had faced to his life.

Our story could have ended differently, but it didn’t. What was I to make of it?

My husband and I left the hospital a day later in the family car we purchased weeks before, fit for a car seat. Like any new mother, I sat in the back, sprawled over our son, ready to shield him from any oncoming danger. A few days later, as we drove from our home to a medical appointment, I became weepy as I tried to describe to my husband how big the world now felt with our small family inside of it.

The first months of my matrescence felt like a strange and tender homecoming to a terrain at once foreign and familiar. In the beginning I felt anxious letting anyone, even my husband, hold him but me. Remembering my birth mother, with whom I was inseparable during my own infancy and who died 30 some years ago, it took weeks before I fully registered that my son was not just my son but also my husband’s.

Since adjusting to the very normal and complex experiences of my postpartum, the learning curve and the meaning I’ve taken away from the possibility that my son might not have survived his birth have come into sharper focus.

I spent years of my life learning how to prioritize myself in order to heal from trauma, years spent avoiding and then grappling with the vulnerability that love asks of all of us behind a veneer of perfectionism and control — but I am now aware that becoming a mother will ask me, over and over again, to surrender these, my tools of survival, and to embrace the risks inherent to love, inherent even still to motherhood.

And though the thought of releasing my grip on perfectionism and control sounds scary and exhausting given all that I have done to get to this point, I also understand that my real work is only now just beginning, that everything I achieved up until birthing our son has granted me a more stable baseline from which to parent, from which to mother.

What could be more vulnerable?

What could be more worth it?

Photo Courtesy Of Mirella Stoyanova

One year later, I still get the urge to organize my son’s toys before he’s done playing with them, to wipe down our kitchen counter before he’s finished throwing every morsel of food off his plate and to plan around his nap time like it’s set in stone (spoiler alert: it’s not).

I also struggle not to hold myself to the impossible standards that are often placed on women of my generation who want both to work and to parent. I have to check my ambition often to make sure I don’t lose sight of the bigger picture.

Beyond the heightened awareness that my entry to motherhood has left me with, it has also recast the standard of my success in terms I never would have thought or expected. Motherhood has asked me to release my grip on control and perfectionism in exchange for something much more valuable but also much more messy: a life that, in its inherent uncertainty, is both beautiful and worthwhile.

I now spin for joy rather than control.

As my son and I walked barefoot recently, through a corner of our backyard filled with wet dirt and pea gravel and tree frogs to be found, I had the thought that while trauma may have altered my upbringing, I am proud that it doesn’t have to alter his.

Support Free Journalism

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch at pitch@huffpost.com.

Support Free Journalism

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

Read more