News

I Grew Up Thinking My Father Didn’t Like Me. It Was Decades Before I Learned The Truth.

In one of my earliest memories of my father, he doesn’t appear at all.

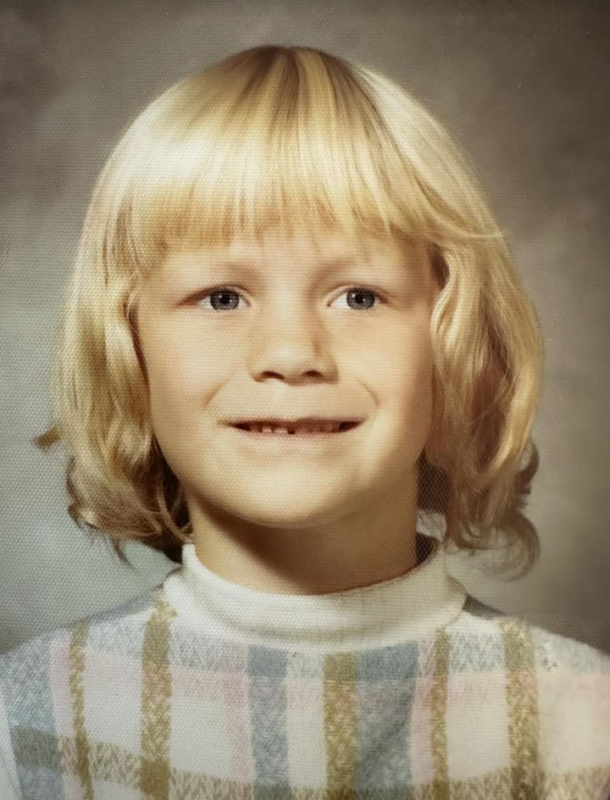

I see only me, a girl of 5 or 6, tiptoeing down a dark hallway toward a closed door, my insides all tied up in knots. Normally I’m a girl who creates commotion, loud and unruly, the kind of kid some might call a lot, but right now I feel like a little. I need something from my father, but I don’t want to bother him. Moments earlier, I told my mother as much, and said, “Oh, honey, don’t be scared. Just go ask him.”

My parents and I lived in a working-class Phoenix neighborhood, in a tract house shaped like a matchbook with three bedrooms. The closed door led to the spare room my father used as his art studio. And while the memory ends before the door opens, I can conjure for you the man behind it: a young man, not much older than 30, with eyes the color of melancholy and feathered hair like a 1970s teen heartthrob, transfixed by the painting in front of him as if under his own spell.

My father taught high school art for a living, but he was also magic. He could

manifest beauty from squishy tubes of paint. He could disappear right before your eyes. He was a closed door, moody and distant. A car pulling out of the driveway, restless and impatient. A faulty water faucet that jumped to scalding with the tiniest of nudges. I didn’t know how to adjust him, so I tried adjusting myself. I tried not to bother him.

If my dad were still alive, it would hurt him to read these words. Because he loved me. Because he never intended for me to feel like a nuisance. So why, then, did I so often feel that way?

This question has taken me decades to answer. Partly because, until relatively recently, crucial information was missing. You can’t put a puzzle together if you don’t have all the pieces. But before I share what I’ve learned about my relationship with my dad, there’s something you should know:

The kids at school didn’t like me much either. And, unlike my father, they meant it. This wasn’t hard to figure out — children aren’t exactly subtle about such things — but I didn’t understand why, so I couldn’t manage to fix what was “wrong” with me. You can’t fix a problem if you don’t know what it is.

While I did well in school, my self-awareness and self-control continued to lag behind my peers throughout high school and into young adulthood. I listened too little and spoke too carelessly and showed up too late. I cried too easily and drank too much and slept with too many boys. I made too many mistakes, and I hated myself for all of it. I hated my parents, too — though I didn’t know why at the time — for letting it happen. Even when I acted out, practically screaming for attention, they never saw how badly I needed their help. And I took all of my rage at their “failure” out on my mother.

She was the safe one — the strong one, really. My dad often seemed exhausted by life, as if trudging through each day out of sheer determination, and he was so sensitive — defensive really isn’t too strong a word — so easily hurt and guarded. We both were, which made talking to him honestly and expressing anger impossible for me. The fear of hurting him, of feeling the pain of his rejection and judgment, paralyzed me. So I protected his feelings and buried mine.

Then I left. At 18, I began a life of wandering and longing that would go on for nearly 20 years — from city to city, man to man, one shiny new dream to the next, forever fueled by the fairytale that this time things would be different.

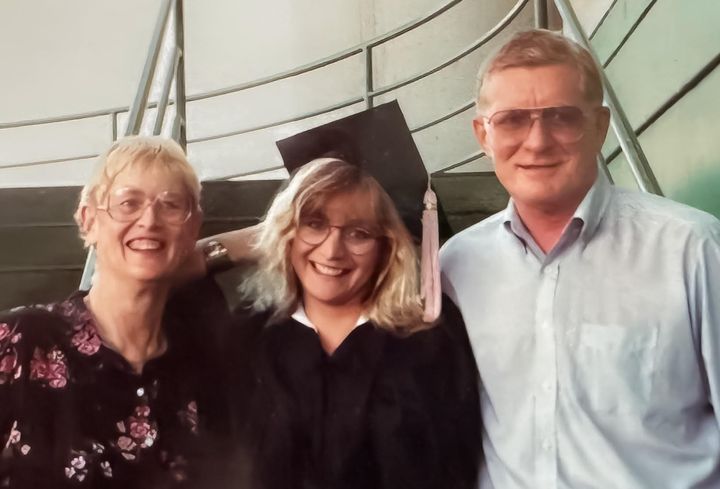

In the early 1990s, while studying journalism at the University of South Florida, I tried therapy for the first time. Though I approached even this sensible endeavor with a magical thinker’s desperate optimism, certain I would be miraculously transformed into a brand-new person, the “confident, reliable, talented, charming and all-round fantastic woman I’ve always longed to be,” I told my journal at the time.

Pretty mind-blowing — though not as mind-blowing as what’s missing from the journals of my 20s: my father! This I blame on an apparently terrible therapist. I have no memory of talking to her about him. Not that I went begging to excavate the long-buried pain of a 6-year-old who believed her dad didn’t like her, but the therapist should have known better.

Several years and a few states later, I did start digging into my relationship with my father, when I returned to therapy in the late ’90s, after moving to New York City. Now in my early 30s, I understood more about my dad’s relationship with his father and the effect of generational trauma, though this information hadn’t come from him. My mother was one I talked to, the one who first revealed how cold and cruel my grandfather had been when my dad was a boy.

But childhood trauma doesn’t explain everything. Mental health is so complex, a tangled web of genetics, brain chemistry and experiences that can be difficult to unravel. Still, even if we never pinpoint exactly where one thread ends and another begins, to understand a person, we at least need to know which threads exist.

For most of his life, my father struggled with depression. This was something I’d sensed as a child — the heaviness he carried — and had come to understand in a vague way as an adult (again, from what my mother told me). But I wouldn’t learn the details until I summoned the courage to talk to him. Through intermittent conversations spread out over two decades — from the first letter I sent him in 2000 through the talks we had not long before his death in 2018 — his story would come together, thread by thread.

My father’s depression began at a young age, even before he started high school in the 1950s, and it only worsened as he grew into an adult. Neither therapy nor the various antidepressants he tried over the years helped much. Some people with depression fall into a category doctors call “treatment resistant,” often because they have an undiagnosed “coexisting condition” — another illness or disorder — that is either the root cause of the depression or exacerbating the symptoms.

You can’t fix a problem if you don’t know what it is.

Back when my father was a kid, very few people knew his coexisting condition existed at all. It would take decades for science to catch up to reality, decades before my dad would pick up a July 1994 issue of Time magazine with a cover that asked: ”Distracted? Disorganized? Discombobulated? Doctors Say You May Have Attention Deficit Disorder: It’s Not Just Kids Who Suffer From It.”

It turns out researchers had discovered that children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (then mostly boys) didn’t “grow out of it,” as per the conventional wisdom of the time. Many continued to really struggle with their symptoms throughout adulthood. As he read the description of what this looked like, my father recognized himself, and soon he became part of the first wave of adults (mostly men) to be diagnosed and treated for ADHD.

In his 50s, he finally understood that a neurodevelopmental disorder, not a lack of intelligence, was the reason he’d had trouble learning to read as a boy, the reason he’d needed my mom’s help to get through college. Imagine how that would feel. Imagine finding out after all those years that you weren’t stupid after all.

ADHD is a complex disorder, but essentially it’s about regulation, the brain’s ability to control a whole slew of important functions — not just attention and impulse, but decision-making, working memory, motivation, planning, prioritizing and emotions. Think of it like that faulty water faucet. Too little pressure causes distraction, forgetfulness and disorganization. Too much pressure causes supercharged emotions and hyperfocus (on something the person finds interesting ― say, painting ― and often at the expense of everything and everyone else). It can even cause hypersensitivity to physical and emotional sensations, so the person feels things — like rejection — more intensely.

And people with ADHD face a lot of rejection. This is in part because many of the behaviors associated with the disorder can really annoy and hurt other people. Things like zoning out while someone is talking, or constantly interrupting, or forgetting important events, or endlessly showing up late, or committing to things and then not following through. Or snapping at someone for no reason. Or melting down like a toddler in public. Think about how you feel when a person, especially an adult, does these things. Does that person seem inconsiderate? Irresponsible? Rude? Unstable?

We all have our moments, but when a friend or a family member has more than their share, when they just can’t seem to get their shit together, don’t you get a little tired of it? Even if you love them, don’t you maybe limit how much time you spend with them?

Most people living with undiagnosed ADHD know they disappoint and hurt others; they just don’t know why they do it. And often, rather than face constant rejection, they do what my father did: They withdraw. They wall themselves off. Maybe they keep their mouths shut so they don’t say the wrong thing. Maybe they self-medicate because it’s all just too painful.

I’m not saying having ADHD sentences a person to misery. Once diagnosed, even severe cases can be treated and managed. Many adults with the disorder can and do learn to thrive, especially now with awareness increasing. But unmanaged ADHD can wreak havoc on a life, causing relationship problems, low self-esteem and chronic demoralization.

Numerous studies have found significantly higher rates of depression among youths and adults with ADHD — an estimated 44% experience a depressive episode before age 30, compared to 25% of their neurotypical peers. Science is still trying to pinpoint why, but it seems increasingly likely that both the emotional toll of living with ADHD and biology play a role. Both ADHD and depression run in families, and researchers who recently dug into piles of genetic research determined a shared genetic risk for the two disorders. They also found that people with ADHD were 30% more likely than neurotypical folks to attempt suicide. Those who also struggled with major depressive disorder were 42% more likely to try to end their lives.

This would not have surprised my dad. In a 2008 email, he told me he’d often wished he were dead.

“I feel so frustrated because I know that without [depression and ADHD], I would have been 50% better at my every endeavor,” he wrote. “I would have been a better father, husband, artist, art teacher, writer, etc. On the other hand, I’ve seen improvements lately and this encourages me to carry on.”

This is why we need to take ADHD seriously. Because, even with a genetic predisposition, the environment we grow up in makes a huge difference in whether genes are expressed. With an early ADHD diagnosis and the help of informed and supportive adults, my dad’s life could have turned out very differently. And by extension, his daughter’s life could have, too.

When I first read that email, I still didn’t understand what ADHD was all about. But I understood what it felt like to wish I would die. I had often fantasized about dying and coming back as someone else — someone better. In my most desperate moments, if a genie had granted me that wish, with a guarantee I’d be reborn as that woman I’d always longed to be, I would have killed myself in a heartbeat. But I didn’t really want to die; I just wanted to be happy.

Over time, with maturity and a lot of therapy, certain aspects of my life did get better. I made lasting friendships, married the man I’ve been with for more than 20 years and became a mother to our beautiful daughter. But I still struggled in many ways — with emotions I often couldn’t control and a brain that seemed more forgetful and distracted than ever — and I continued to blame myself for these “faults” until I finally sought help again.

In 2017, I went to a neuropsychologist, and soon I became part of a new wave of adults discovering their ADHD at 30 or 40 or 50, many of them women whose condition had gone unrecognized their whole lives. Because our symptoms often look different from men’s, no one thought to consider that we might have the same neurodevelopmental disorder as all those hyper little boys.

At 51 years old, eerily close to the same age as my dad when he was diagnosed, I finally had the missing puzzle piece that explained so much about me — about us. I understand now how an emotionally unregulated, hypersensitive parent might be easily annoyed and exhausted by a kid who’s a lot. And how a child might misinterpret the behaviors of a parent who’s often distracted, impatient and irritable.

Today, when I reread that email, I understand the frustration and regret my dad was expressing. And I wonder what our relationship might have been like in a world where problems get fixed because you know what they are.

Perhaps a little more often it would have looked like another long-ago memory, where I’m around 5 or 6. This one begins with my dad and me together in the living room. He’s been helping me get into a pair of red tights that go with the polka-dot jumper I’m wearing, but now I’m standing up and the crotch is sagging in that annoying way tights do when they’re not pulled up properly. I hate the way it feels. “They’re not on!” I tell him.

I’m tired and cranky, but he just smiles an amused smile, takes hold of the tights by the waistband and pulls up, lifting me off the ground a little as they slide into place. This makes me giggle, and seeing that, he holds me around the waist and hoists me up above his head. He begins to spin, around and around, and I am flying and shrieking with laughter and he’s grinning. When my feet hit the floor, I feel dizzy and delirious and my words spill out, loud and crazed. “Do it again! Please, do it again!”

And in this moment, I am not a nuisance. In this moment, he lifts me again high in the air, and again I am flying, and we are magic.

CJ Clouse’s parents met in group therapy — in retrospect a clear sign that writing personal stories related to family dysfunction and mental health is her true calling. Despite these portentous origins, she has spent most of her writing career as a journalist, most recently as a freelancer focused on the environment and sustainability. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, HuffPost, GreenBiz, Mongabay, Barron’s, National Geographic, The Forge, Southeast Review and many others. She’s currently at work on a memoir, which chronicles her search for the truth about her maternal grandmother, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia and institutionalized at age 27. CJ lives in Brooklyn with her husband and daughter.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch at pitch@huffpost.com.

If you or someone you know needs help, call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org for mental health support. Additionally, you can find local mental health and crisis resources at dontcallthepolice.com. Outside of the U.S., please visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention.

Read more